Delving into BERT Representations to Explain Sentence Probing Results

This is a post for the EMNLP 2021 paper Exploring the Role of BERT Token Representations to Explain Sentence Probing Results.

We carry out an extensive gradient-based attribution analysis to explain probing performance results from the viewpoint of token representations. Based on a set of probing tasks we show that:

- while most of the positional information is diminished through layers of BERT, sentence-ending tokens are partially responsible for carrying this knowledge to higher layers in the model.

- BERT tends to encode verb tense and noun number information in the \(\texttt{##s}\) token and that it can clearly distinguish the two usages of the token by separating them into distinct subspaces in the higher layers.

- abnormalities can be captured by specific token representations, e.g., in two consecutive swapped tokens or a coordinator between two swapped clauses.

What’s Wrong with Standard Probing?

Probing is one of the popular analysis methods, often used for investigating the encoded knowledge in language models. This is typically carried out by training a set of diagnostic classifiers that predict a specific linguistic property based on the representations obtained from different layers.

Recent works in probing language models demonstrate that initial layers are responsible for encoding low-level linguistic information, such as part of speech and positional information, whereas intermediate layers are better at syntactic phenomena, such as syntactic tree depth or subject-verb agreement, while in general semantic information is spread across the entire model. Despite elucidating the type of knowledge encoded in various layers, these studies do not go further to investigate the reasons behind the layer-wise behavior and the role played by token representations. Analyzing the shortcomings of pre-trained language models requires a scrutiny beyond the mere performance in a given probing task.

So, we extend the layer-wise analysis to the token level in search for distinct and meaningful subspaces in BERT’s representation space that can explain the performance trends in various probing tasks.

Methodology

Our analytical study was mainly carried out on a set of sentence-level probing tasks from SentEval. We used the test set examples for our evaluation and in-depth analysis.

For computing sentence representations for layer \(l\), we opted for a simple unweighted averaging (\(h^l_{Avg}\)) of all input tokens (except for padding and \(\texttt{[CLS]}\) token). This choice was due to our observation that the mean pooling strategy retains or improves \(\texttt{[CLS]}\) performance in most layers in our probing tasks (cf. Appendix A.1 in the paper). Moreover, the mean pooling strategy simplifies our measuring of each token’s attribution, discussed next.

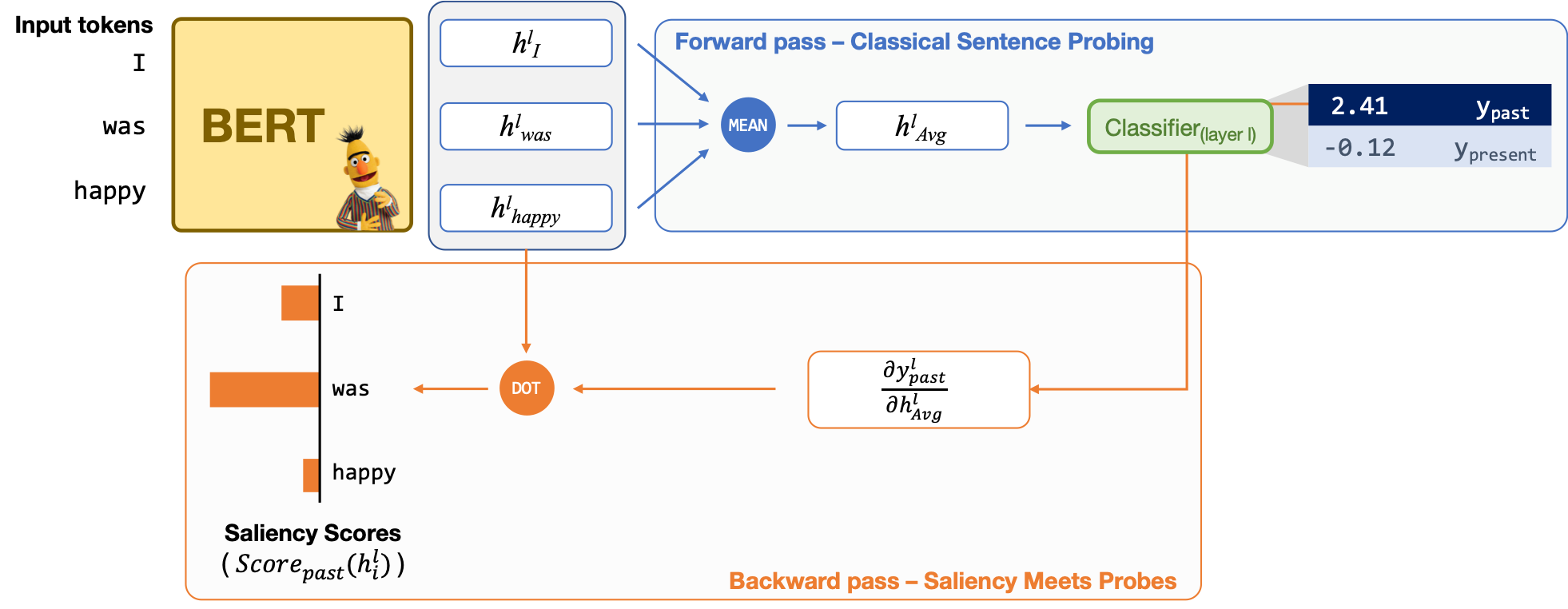

Saliency Meets Probes

We leveraged a gradient-based attribution method in order to enable an in-depth analysis of layer-wise representations with the objective of explaining probing performances. Specifically, we are interested in computing the attribution of each input token to the output labels. This is usually referred to as the saliency score of an input token to classifier’s decision.

We adopt the method of Yuan et al. (2019) for our setting and compute the saliency score for the \(i^{\text{th}}\) representation in layer \(l\), i.e., \(h^l_i\), as:

\[\begin{equation} \label{eq:score} Score_c(h^l_i) = \frac{\partial y^l_c}{\partial h_{Avg}^l} \cdot h^l_i \end{equation}\]where \(y^l_c\) denotes the probability that the classifier assigns to class \(c\) based on the \(l^{\text{th}}\)-layer representations. Given that our aim is to explain the representations (rather than evaluating the classifier), we set \(c\) in the equation as the correct label. This way, the scores reflect the contributions of individual input tokens in a sentence to the classification decision.

Note that using attention weights for this purpose can be misleading given that raw attention weights do not necessarily correspond to the importance of individual token representations.

Probing Explanation

To show the usefulness of our proposed analysis method in revealing the role of token representations, thereby explaining probing results, we conduct our experiments on a set of surface, syntactic and semantic probing tasks. Based on the most attributed tokens, we then investigate the reasons behind performance variations across layers.

Sentence Length

In this surface-level task we probe the representation of a given sentence in order to estimate its size, i.e., the number of words (not tokens) in it. To this end, we used SentEval’s SentLen dataset, but changed the formulation from the original classification objective to a regression one which allows a better generalization due to its fine-grained setting. The diagnostic classifier receives average-pooled representation of a sentence as input and outputs a continuous number as an estimate for the input length.

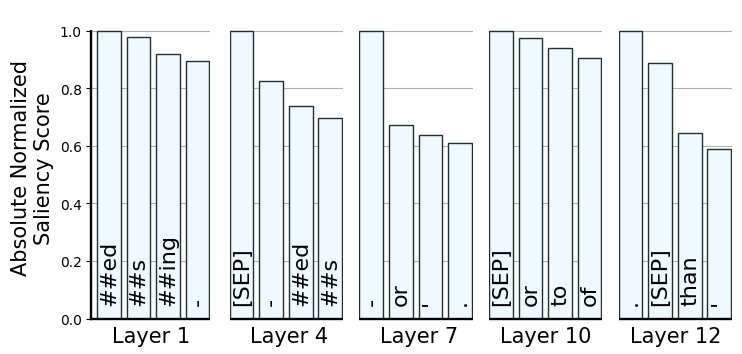

Rounding the regressed estimates and comparing them with the gold labels in the test set, we can observe a significant performance drop from 0.91 accuracy in the first layer to 0.44 in the last layer. Given that the ability to encode the exact length of input sentences is not necessarily a critical feature, and this decay is not surprising due to the existing previous studies, we do not focus on layer-wise performance results and instead discuss the reason behind the performance variations across layers. To this end, we calculated the absolute saliency scores for each input token in order to find those tokens that played pivotal role while estimating sentence length.

Sentence ending tokens retain positional information.

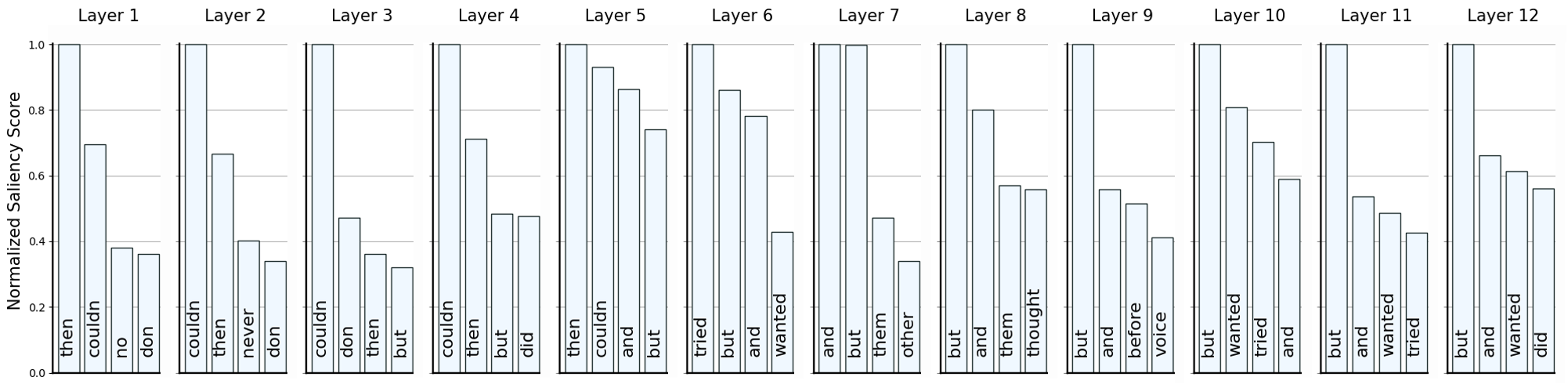

This figure shows tokens that most contributed to the probing results across different layers according to the attribution analysis. Clearly, finalizing tokens (e.g. \(“\texttt{[SEP]}”\) and \(“\texttt{.}”\)) are the main contributors in the higher layers.

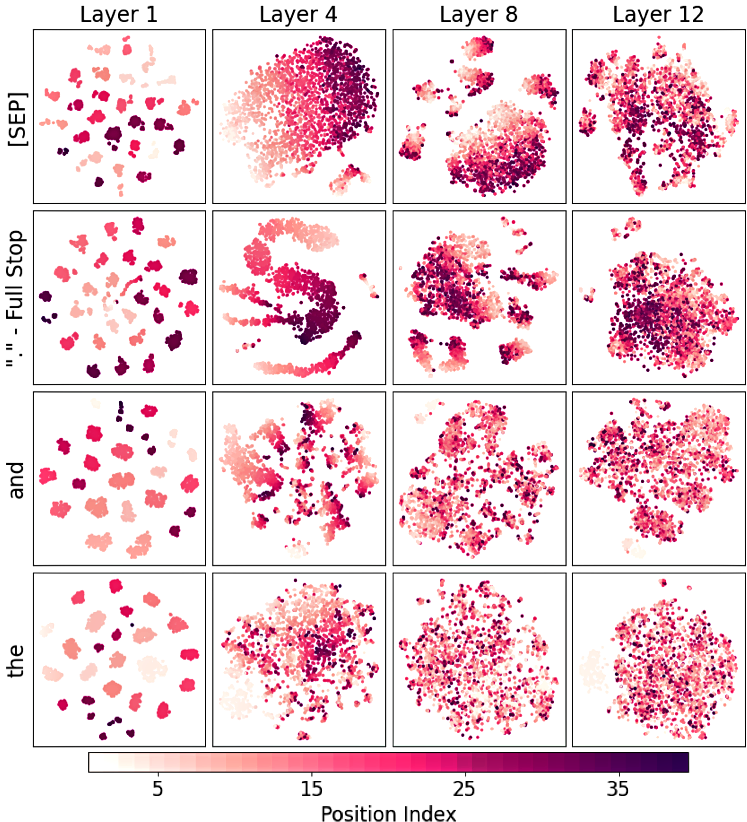

Here are t-SNE plots of the representations of four selected high frequency tokens (\(“\texttt{[SEP]}”\), \(“\texttt{.}”\) full stop, \(“\texttt{the}”\), \(“\texttt{and}”\)) in different sentences.

Colors indicate the corresponding token’s position in the sentence (darker colors means higher position index). Finalizing tokens (e.g., \(“\texttt{[SEP]}”\), \(“\texttt{.}”\)) preserve distinct patterns in final layers, indicating their role in encoding positional information, while other (high frequency) tokens exhibit no such behavior.

Verb Tense and Noun Number

This analysis inspects BERT representations for grammatical number and tense information. For this experiment we used the ObjNum and Tense tasks: the former classifies the direct object of the main clause according to its number, i.e., singular (NN) or plural (NNS), whereas the latter checks whether the main-clause verb is labeled as present or past. Let’s look at an example from each probing task:

ObjNum:

Tense:

In Tense task, each sentence may include multiple verbs, subjects, and objects, while the label is based on the main clause (Conneau et al., 2018).

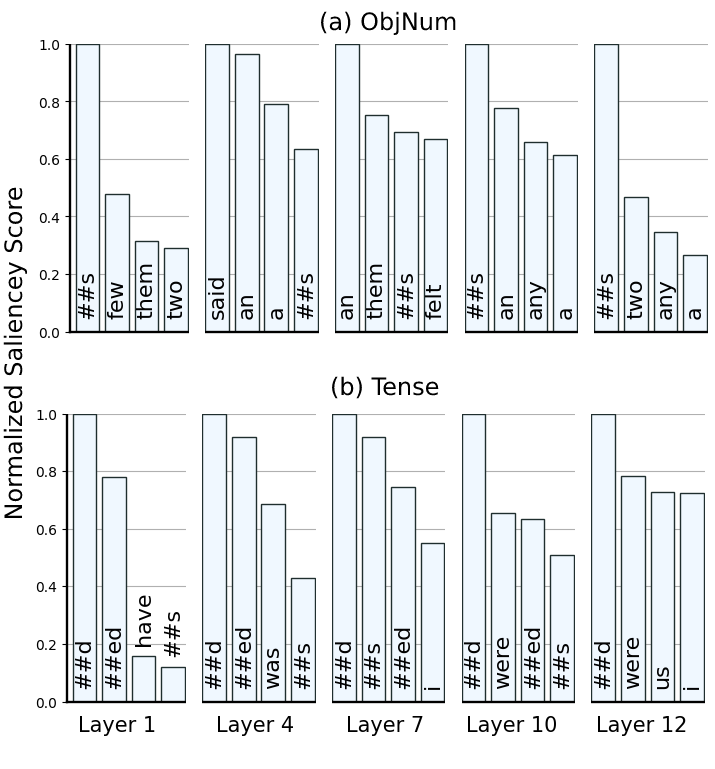

Articles and ending tokens (e.g., \(\texttt{##s}\) and \(\texttt{##ed}\) ) are key playmakers.

On both tasks, BERT preserves a consistently high performance (> 0.82 accuracy) across all layers. Our Attribution analysis reveals that article words (e.g., \(“\texttt{a}”\) and \(“\texttt{an}”\)) and the ending \(\texttt{##s}\) token, which makes out-of-vocab plural words (or third person present verbs), are among the most attributed tokens in the ObjNum task. This shows that these tokens are mainly responsible for encoding object’s number information across layers.

On both tasks, BERT preserves a consistently high performance (> 0.82 accuracy) across all layers. Our Attribution analysis reveals that article words (e.g., \(“\texttt{a}”\) and \(“\texttt{an}”\)) and the ending \(\texttt{##s}\) token, which makes out-of-vocab plural words (or third person present verbs), are among the most attributed tokens in the ObjNum task. This shows that these tokens are mainly responsible for encoding object’s number information across layers.

As for the Tense task, the figure shows a consistently high influence from verb ending tokens (e.g., \(\texttt{##ed}\) and \(\texttt{##s}\)) across layers which is in line with performance trends for this task and highlights the role of these tokens in preserving verb tense information.

\(\texttt{##s}\) — Plural or Present?

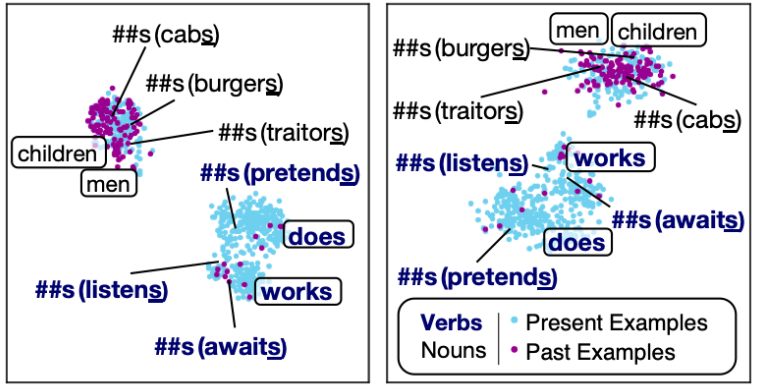

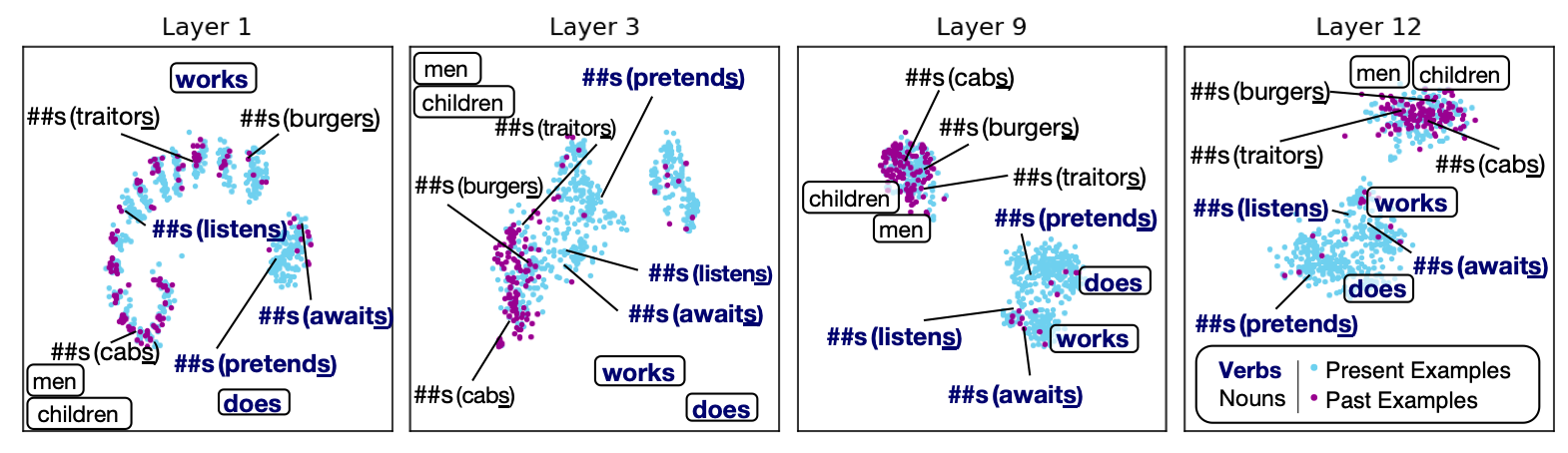

The \(\texttt{##s}\) token proved influential in both tense and number tasks. The token can make a verb into its simple present tense (e.g., read → reads) or transform a singular noun into its plural form (e.g., book → books). We further investigated the representation space to check if BERT can distinguish this nuance. Results are shown here:

Colors indicate whether the token occurred in present- or past-labeled sentence in the Tense task. For the sake of comparison, we also include two present verbs without the \(\texttt{##s}\) token (i.e., \(“\texttt{does}”\) and \(“\texttt{works}”\)) and two irregular plural nouns (i.e., \(“\texttt{men}”\) and \(“\texttt{children}”\)), in rounded boxes. After the initial layers, BERT recognizes and separates these two forms into two distinct clusters (while BERT’s tokenizer made no distinction among different usages). The distinction between the two different usages of the token (as well as the tense information) is clearly encoded in higher layer contextualized representations.

Inversion Abnormalities

For this set of experiments, we opted for SentEval’s Bi-gram Shift and Coordination Inversion tasks which respectively probe model’s ability in detecting syntactic and semantic abnormalities. The goal of this analysis was to to investigate if BERT encodes inversion abnormality in a given sentence into specific token representations.

Word-level inversion

Bi-gram Shift (BShift) checks the ability of a model to identify whether two adjacent words within a given sentence have been inverted. Let’s look at the following sentences and corresponding labels from the test set:

Probing results shows that the higher half layers of BERT can properly distinguish this peculiarity. Similarly to the previous experiments, we leveraged the gradient attribution method to figure out those tokens that were most effective in detecting the inverted sentences. Given that the dataset does not specify the inverted tokens, we reconstructed the inverted examples by randomly swapping two consecutive tokens in the original sentences of the test set, excluding the beginning of the sentences and punctuation marks.

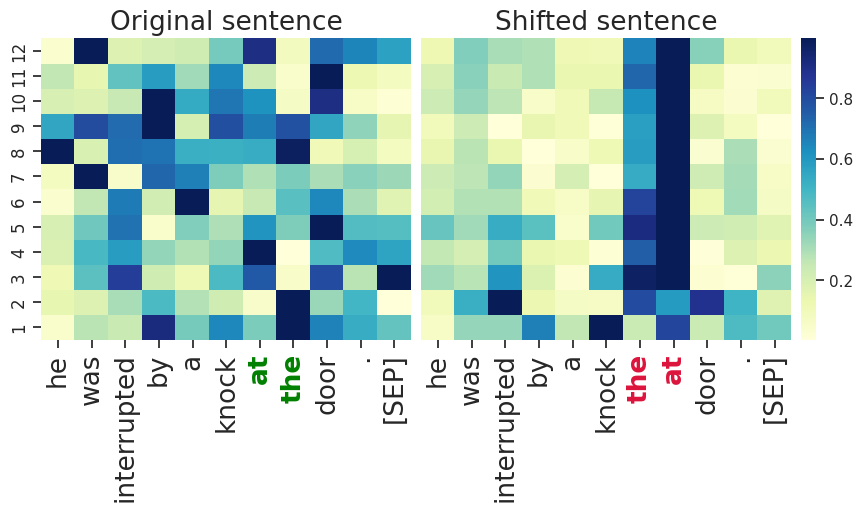

Our attribution analysis shows that swapping two consecutive words in a sentence results in a significant boost in the attribution scores of the inverted tokens. As an example, the subsequent figure depicts attribution scores of each token in a randomly sampled sentence from the test set across different layers. The classifier distinctively focuses on the token representations for the shifted words, while no such patterns exists for the original sentence.

Our attribution analysis shows that swapping two consecutive words in a sentence results in a significant boost in the attribution scores of the inverted tokens. As an example, the subsequent figure depicts attribution scores of each token in a randomly sampled sentence from the test set across different layers. The classifier distinctively focuses on the token representations for the shifted words, while no such patterns exists for the original sentence.

To verify if this observation holds true for other instances in the test set, we carried out the following experiment.

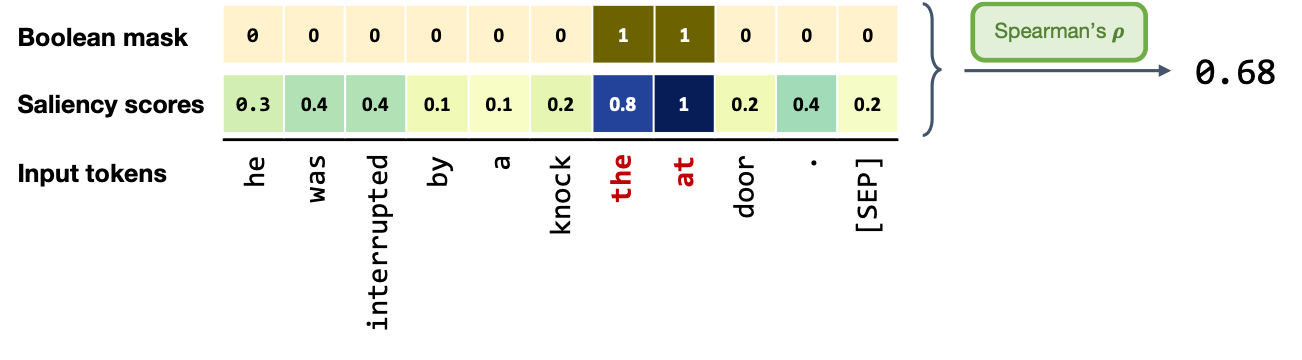

For each given sequence \(X\) of \(n\) tokens, we defined a boolean mask \(M =[m_1 , m_2 , ..., m_n]\) which denotes the position of the

inversion according to the following condition:

\(\begin{equation}

m_i =

\begin{cases}

1, & x_i \in V \\

0, & \textrm{otherwise} \

\end{cases}

\end{equation}\)

where \(V\) is the set of all tokens in the shifted bi-gram (\(|V|\ge2\), given BERT’s sub-word tokenization).

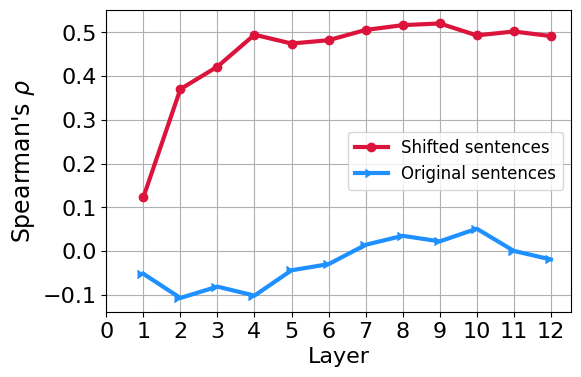

Then we computed the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of the attribution scores with \(M\) (a one-hot indicating shifted indices) for all examples in the test set across all layers. We observe that in altered sentences the correlation significantly grows over the first few layers which indicates model’s increased sensitivity to the shifted tokens.

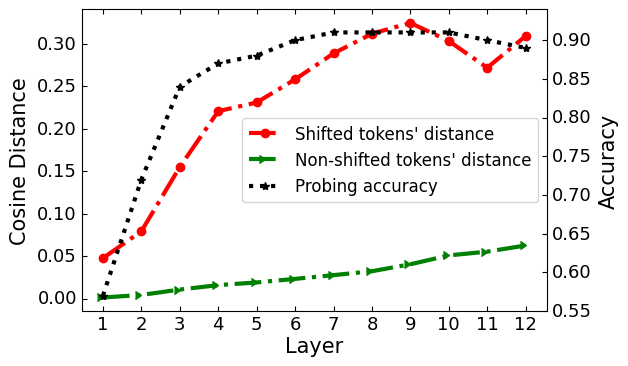

We hypothesize that BERT implicitly encodes abnormalities in the representation of shifted tokens. To investigate this, we computed the cosine distance of each token to itself in the original and shifted sentences. This figure shows layer-wise statistics for both shifted and non-shifted tokens. The trend for the shifted token distances highly correlates with that of probing performance, supporting our hypothesis of BERT encoding abnormalities in the shifted tokens.

We hypothesize that BERT implicitly encodes abnormalities in the representation of shifted tokens. To investigate this, we computed the cosine distance of each token to itself in the original and shifted sentences. This figure shows layer-wise statistics for both shifted and non-shifted tokens. The trend for the shifted token distances highly correlates with that of probing performance, supporting our hypothesis of BERT encoding abnormalities in the shifted tokens.

To investigate the root cause of this, we took a step further and analyzed the building blocks of these representations, i.e., the self-attention mechanism (read the paper for details).

Phrasal-level inversion

The Coordination Inversion (CoordInv) task is a binary classification that contains sentences with two coordinated clausal conjoints (and only one coordinating conjunction). In half of the sentences the clauses’ order is inverted and the goal is to detect malformed sentences at phrasal level. Two examples of these malformed sentences are:

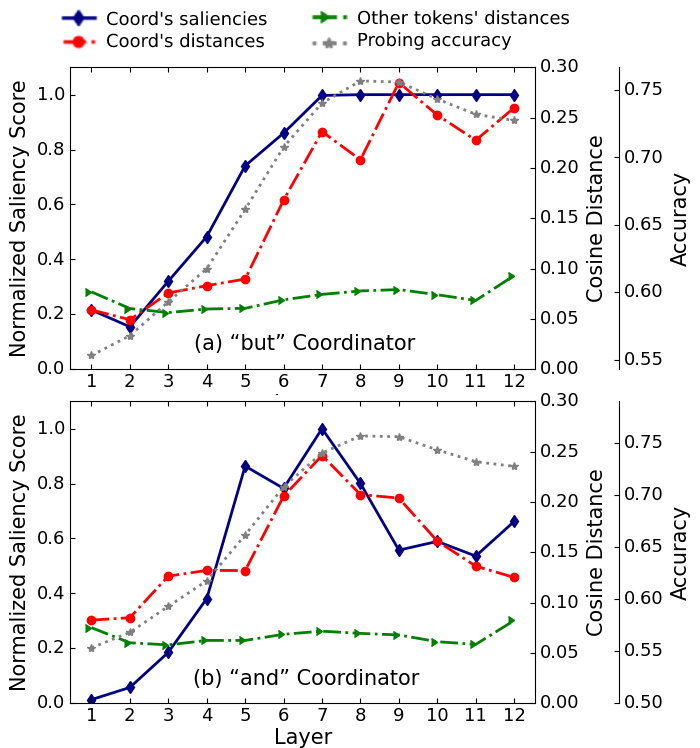

BERT’s performance on this task increases through layers and then slightly decreases in the last three layers. We observed that the attribution scores for \(“\texttt{but}”\) and \(“\texttt{and}”\) coordinators to be among the highest and that these scores notably increase through layers. We hypothesize that BERT might implicitly encodes phrasal level abnormalities in specific token representations.

Odd Coordinator Representation

To verify our hypothesis, we filtered the test set to ensure all sentences contain either a \(“\texttt{but}”\) or an \(“\texttt{and}”\) coordinator, since no sentence appears with both labels in the dataset. Then, we reconstructed the original examples by inverting the order of the two clauses in the inverted instances.

Feeding this to BERT, we extracted token representations and computed the cosine distance between the representations of each token in the original and inverted sentences. The subsequent figure shows these distances, as well as the normalized saliency score for coordinators (averaged on all examples in each layer), and layer-wise performance for the CoordInv probing task.

Feeding this to BERT, we extracted token representations and computed the cosine distance between the representations of each token in the original and inverted sentences. The subsequent figure shows these distances, as well as the normalized saliency score for coordinators (averaged on all examples in each layer), and layer-wise performance for the CoordInv probing task.

Surprisingly, all these curves exhibit a similar trend. As we can see, when the order of the clauses are inverted, the representations of the coordinators \(“\texttt{but}”\) or \(“\texttt{and}”\) play a pivotal role in making sentence representations distinct from one another while there is nearly no change in the representation of other words. This observation implies that BERT somehow encodes oddity in the coordinator representations (corroborating part of the findings of our previous analysis of BShift task in the previous part).

Conclusion

We provided an analysis on the representation space of BERT in search for distinct and meaningful subspaces that can explain probing results. Based on a set of probing tasks and with the help of attribution methods we showed that BERT tends to encode meaningful knowledge in specific token representations (which are often ignored in standard classification setups), allowing the model to detect syntactic and semantic abnormalities, and to distinctively separate grammatical number and tense subspaces.

Our approach in using a simple diagnostic classifier and incorporating attribution methods provides a novel way of extracting qualitative results based on multi-class classification probes. This analysis method could be easily applied to probing various deep pre-trained models on various sentence level tasks. We hope this method will spur future probing studies in other evaluation scenarios. Future work might explore to investigate how these subspaces are evolved or transformed during fine-tuning and whether being beneficial at inference time to various downstream tasks or to check whether these behaviors are affected by different training objectives or tokenization strategies.